Reviewed by Bethany M. Dunbar

copyright the Chronicle 4-3-2013

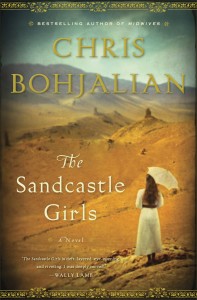

The Sandcastle Girls, by Chris Bohjalian, published in the United States by Doubleday, 2012, hardcover, 293 pages, $25.95.

The Sandcastle Girls by Chris Bohjalian is a beautiful story of love and war and genocide.

First published last year, the book is about to come out in paperback just as Armenians will mark the ninety-eighth anniversary of April 24, Genocide Memorial Day. On that date 98 years ago, Armenian intellectuals, community leaders, and the editors and staff of the leading Armenian newspaper were rounded up, arrested and imprisoned — to be killed a few months later.

My own awareness of the systematic killing of 1.5-million Armenians at the hands of the Turkish army came about not from history classes in high school or college, but from an annual letter to the editor the Chronicle used to receive this time of year. Written by Tom Azarian, who used to live in Calais, the letter was sent to recognize the horrors of these events. We always published it.

The Sandcastle Girls is called Mr. Bohjalian’s most personal novel because his own heritage is Armenian. This is his fourteenth novel, and his name is often found on the New York Times bestseller list. He lives in Vermont and writes a column for the Burlington Free Press called Idyll Banter that is often funny and always interesting.

His novels are usually gripping, with strong characters and plots and often a mystery or surprising twist.

The Sandcastle Girls definitely fits that description.

In the book’s prologue, an ordinary working suburban New York woman, a writer named Laura Petrosian, recalls her childhood visits with her grandparents, who had exotic hookah pipes and liked to eat lamb and Cocoa Puffs.

As was so common for that generation, sadness of the past was never discussed. Their life seems to be a happy one. The children sing; the protagonist’s grandmother even belly dances:

Regardless, the belly dancing — as well as my grandfather’s affection for his chubby grandchildren — does suggest that their house existed beneath a canopy of playfulness and good cheer. Sometimes it did. But equally often there was an aura of sadness, secrets, and wistfulness. Even as a child I detected the subterranean currents of loss when I would visit.

From there, the book travels in time back to the grandmother’s mission to Aleppo, Syria, where skeletal Armenians had been marched through the desert and were being kept until they died on their own, or taken away.

She meets the handsome young soldier, Armen.

In the middle of the horrors of this war, there are good people, people who want to help the victims and those who want to get the word out about what is being done.

Photos are taken. Miraculously, some glass plates — images of the horrors of the genocide — are not destroyed. Huge risks allow these images to be kept and to get out for the world to see.

One of these images becomes a key for Laura Petrosian so many years later as she tries to decipher her family’s history. She finds it and some of her grandmother’s letters in a museum exhibit.

The Sandcastle Girls is not an easy or comfortable book to read. When Laura’s grandmother, Elizabeth Endicott, first arrives in Aleppo as a young missionary to help Armenian refugees, she is not prepared for what she will see:

Approaching from down the street is a staggering column of old women, and she is surprised to observe they are African. She stares, transfixed. She thinks of the paintings and drawing she has seen of American slave markets in the south from the 1840s and 1850s, though weren’t those women and men always clothed — if only in rags? These women are completely naked, bare from their feet to the long drapes of matted black hair. And it is the hair, long and straight though filthy and impossibly tangled, that causes her to understand that these women are white — at least they were once — and they are, in fact, not old at all. Many might be her age or even a little younger. All are beyond modesty, beyond caring. Their skin has been seared black by the sun or stained by the soil in which they have slept or, in some cases, by great yawning scabs and wounds that are open and festering and, even at this distance, malodorous. The women look like dying wild animals as they lurch forward, some holding on to the walls of the stone houses to remain erect. She has never in her life seen people so thin and wonders how in the name of God their bony legs can support them. Their breasts are lost to their ribs. The bones of their hips protrude like baskets.

“Elizabeth, you don’t need to watch,” her father is saying, but she does. She does.

How do we learn about our ancestors’ past? We might ask our grandparents, read their letters, read history books, or pick up a novel. While the characters and plot examples of a novel might not be “true” in the surface sense of the word, it could still provide the truest account of what that time and place felt like.

With The Sandcastle Girls, Chris Bohjalian has written a haunting, gorgeous, story — as true as it can be.

contact Bethany M. Dunbar at [email protected]

For more free articles from the Chronicle like this one, see our Reviews pages. For all the Chronicle’s stories, pick up a print copy or subscribe, either for print or digital editions.