Crossing Jack Brook: Love and Death in the Woods, by Paul Lefebvre. Published by Beck Pond Books. 169 pages. Paperback. $20.

Your odds of finding a four-leaf clover on your first try are roughly on a par with those of being injured by a toilet seat, about one in 10,000. You have at least a seven times better chance of becoming President of the United States than winning at Powerball with your first ticket, though in the former case multiple variables come into play, such as whether and where you went to college and in which rest room, ladies’ or gents’, you’re entitled to test your luck with a toilet seat.

However you choose to place your bets, few factors reliably alter the odds of surviving the love of your life. No matter where you live, how many minutes a day you exercise, or whether your beloved is a Methodist, a lesbian, or a canary, those odds are essentially the same. One in two.

For that reason, books about grieving a dear companion’s death — Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, C. S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed, and, closer to home, Edie Clark’s The Place He Made and Donald Hall’s Without — are among the most useful on the shelves. That doesn’t mean they’re always the most readable or will all deserve to be called beautiful. Chronicle reporter and columnist Paul Lefebvre’s Crossing Jack Brook is both.

It’s also three captivating stories for the price of one. The most prominent is about the sickness and death of the artist Elin K. Paulson, Lefebvre’s long-time partner, which he tells without a trace of morbidity. Nicknamed “Rocky” for her passion for collecting rocks, Paulson comes across as a fascinatingly complex character: “a bohemian woman” who did not like to be called a hippie, a nature-lover who did not care to grow a garden, a pacifist who loved John Brown. We can wonder about all of that, but we never wonder why Lefebvre loved Paulson. After only a few pages, we’re pretty fond of her too.

In the symbolism of their love affair, Lefebvre fleshes out his second big story: the initial clash and ultimate fusion of two tribes that occurred when the migratory counterculture of the 1960s met the indigenous counterculture of the Northeast Kingdom. Lefebvre and Paulson come across as representative, if highly individualized, members of their respective tribes:

he an Island Pond native of French Canadian extraction with railway men and loggers in his family and roots in the Kingdom that go back as far as 1799; she the down-country daughter of a Catholic-Worker couple, artisans and homesteaders devoted to a movement that was talking about peace, love, and communal living before there were television sets and atom bombs.

Mixing these diverse elements, Lefebvre gives us a darker, more viscous narrative than that fancy-grade syrup that often gets poured over things “Vermont.” He also introduces us to a motley cast of characters: the Count and the Commissioner, “the girls of Lost Nation,” and the denizens of Mad Brook Farm, will-o’-the-wisp hermits and stoned entrepreneurs, gun-packing truckers and the activist priest Bob Castle, aka “Reverend Slick.” At Lefebvre’s hunting camp we hear “anthems to those who have prepared liver and onions on a cookstove, brought bottles of whiskey to Thanksgiving Day dinner, and left the air charged with the pungent odor of Hoppes #9 oil from cleaning their guns at the kitchen table.” Well, many of us have been to a hunting camp, but few of us could describe it like Lefebvre.

So we are not surprised that the third main story of Crossing Jack Brook is about becoming a writer, not only as a way of making a living but also as a way of fighting for one’s life. The theme is clear from his first paragraph:

“When the woman I lived with became ill with cancer in 2005, I began writing about it in a column I had been writing for a weekly newspaper in northern Vermont. When she died about nine months later, I continued to write about her because it was the only thing I could do. I am not a religious man or a deeply spiritual one, but for years I have earned a living as a reporter and have come to rely on the power of words.”

Lefebvre’s columns about Paulson, their adventures together, and other features of their shared life in the Kingdom are interspersed throughout the book, dated and titled as they were when they debuted in the Chronicle. Some readers might wish that Lefebvre had taken apart these pieces and reworked the material into one seamless whole. I happen not to be one of them. The juxtaposition of what Lefebvre wrote in his columns and what he writes in Crossing Jack Brook adds much to the texture — and pleasure — of his narrative. In a book that is nothing if not a memoir, the technique works like memory itself, moving us backwards and forward in time.

We move easily because he keeps things clear. Lefebvre is an unpretentious stylist, a straight shooter, never sentimental but unafraid of revealing his heart. Like the best prose writers in what William Carlos Williams called “the American grain,” he knows about real stuff: how to pitch a tent, fell a tree, build a deck. He also knows the stuff of history: You will learn about how ice used to be harvested on Island Pond and the etiquette of old logging camps. You will even learn a thing or two about the Civil War.

And you will hear some funny stories. Perhaps my favorite has to do with a chimney fire that erupts at the ramshackle house of one of the author’s drinking buddies just as they’re about to leave for a night at the bar. “The fire will either burn out or the place will burn down,” his friend says. “We’ll find out later.” So off they go.

The result of Lefebvre’s use of lore and laughter is that we experience none of the claustrophobia that we’d expect from a book informed by a terminal illness. (Nor, I’m relieved to say, is Lefebvre the type of eulogist who uses humor in an attempt to make mortality sound cute.) Much of this expansiveness is achieved through the deft characterization of Paulson herself. She is never less than a lively presence. The writer Dorothy Parker’s famous retort to the news that Calvin Coolidge had died — “How can they tell?” — could never apply to Elin Paulson.

I never knew her, by the way, and except for reading some of Lefebvre’s columns and buying fresh fish from him in Newport many years ago (only lately did I realize that the wordsmith and the fishmonger were the same guy), I don’t know him either. But his account of their life together reminds me of men and women I met when I first arrived in the Kingdom — too late, I’m afraid, and too conventional to know their world well, but impressed by it from a distance and, more lately, saddened by a sense of its passing. For Lefebvre that sense is even stronger.

“[H]ome for the past year was beginning to resemble more and more a place where my friends were dying. More and more a place I feared I no longer knew. The Kingdom I knew was shrinking. Land on both sides of the road to my house had been posted against trespassing. A chain had been strung and locked across the road to hunting camp.” It’s much to the author’s credit that he is able to convey a profound sense of loss even as he restores our awareness of what hasn’t yet and needn’t ever be lost completely.

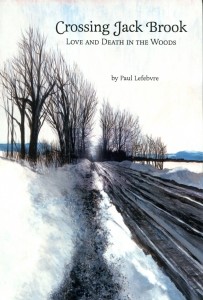

The artwork accompanying Lefebvre’s text lends a hand in this. The striking cover image of Elizabeth Nelson’s painting of a rutted Kingdom road in early spring opens onto a gallery of color photographs, some of Lefebvre’s and Paulson’s family and friends, many of her magical paintings and picture poems (reminiscent of Kenneth Patchen and Paul Klee), a closing shot of her decorated grave. Stained glass by Paulson’s father, Carl, and portraits of her by the painter Peter Miles (along with a photo of Miles himself) make for a fitting artist’s memorial. This is not a coffee table book by any stretch, but for a while after I’d finished reading it, I kept it close to where I drink my coffee, because I liked waking up with the pictures.

Needless to say (at least for anyone who knows Lefebvre or his previous writings), Crossing Jack Brook is not a how-to manual about surviving grief. When I called it useful before, I didn’t mean that it aimed to be. It aims to be true, nothing less or more, and we trust it because the truth it discovers is complicated. At one point during his bereavement, the gregarious Lefebvre exhorts himself to greater self-reliance:

“Usually I go to town on Sunday mornings, get coffee and a doughnut, pick up a paper, and begin a round of visiting friends. Some Sundays we take rides through the woods or to camp or sometimes we do nothing at all except sit around, drink beer and talk. It is nearly always enjoyable and it fills in the time. But this morning I pulled up short. Look to yourself for a change, I said. Stop running away.”

Yet, in looking to himself “for a change,” he also finds a deeper sense of human solidarity and purpose, including the courage to call wisdom by its rightful name.

“Thankfully, not all wisdom comes with great loss — who could endure it if it were so? — yet there is a wisdom that death demands as its own. And while grief may fling us into loneliness, it seems equally true that it welds us to a common lot. Time is short, I tell myself. Honor the dead by the life you lead.”

In Lefebvre’s case, “the life you lead” includes the words you write. In a column he wrote in 2007, and includes near the end of Crossing Jack Brook, he says, “For the first few months, I carried Rocky’s death with me at nearly every step. Anything short of that raised the fear I might lose her. Now nearly 18 months later, I know she will never be lost to me. I know where she resides.”

Thanks to Lefebvre’s stirring tribute, she also resides a little in us, and the odds of our forgetting her are close to none.

Garret Keizer’s most recent book is Privacy (2012).

For more free articles from the Chronicle like this one, see our Reviews pages. For all the Chronicle’s stories, pick up a print copy or subscribe, either for print or digital editions.