copyright the Chronicle March 19, 2014

by Joseph Gresser

If a bill passed last week by the Vermont Senate becomes law, it will be the latest step in Vermont’s very long struggle to find new, and better, ways to deal with criminals. That struggle began about 20 years ago, with a group of young idealists, led by a visionary Westmore man, reshaping how justice is meted out.

The recently approved Senate bill would allow some offenders — primarily those who pose no threat to public safety — the option of participating in a nontraditional program, such as the community justice program that operates in Newport.

Its intent is “that law enforcement officials and criminal justice professionals develop and maintain programs at every stage of the criminal justice system to provide alternatives to a traditional punitive criminal justice response….”

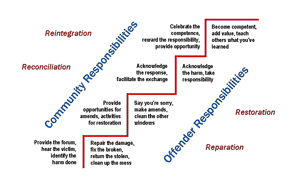

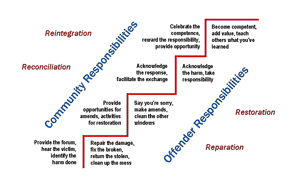

In the nontraditional reparative justice program, community volunteers work with an offender to develop a plan for making amends to the victims of his crime and to repair the damage done by his actions.

That program was developed about two decades ago by a group of young workers at the state Department of Corrections (DOC), with support from several governors and an important contribution from a longtime resident of Westmore, Bill Page.

In the 1970s the nation was seized by a fear of violent crime, and a concern that prisons were not fulfilling the intended purpose of rehabilitation. John Martinson, a noted researcher on the subject, grew pessimistic about the results of all the programs he investigated.

He wrote an article for the magazine Public Interest setting out his findings, an article whose conclusion, usually summarized under the heading “Nothing works,” was spread throughout the popular media.

Around the country, prisons were generally seen only as a means to keep offenders from harming law-abiding citizens. Legislators followed the public mood and voted for increasingly harsh sentences for all manner of offenses.

A group of new officials at the Vermont DOC, however, thought they could find a solution to what seemed an intractable problem.

“We were arrogant, brash and young enough not to know better,” recalled John Perry in a recent telephone interview. Mr. Perry retired from the DOC as director of planning in 2011. “We thought we could make a difference,” he said.

They began in ignorance.

“We knew crime was increasing — increasing like crazy in the late ’70s and ’80s,” Mr. Perry said.

What the young officials at the DOC did not know was that the increase was in reported crime, not actual crime.

In the late ’60s and early ’70s, Vermont experienced an influx of new residents coming from other parts of the country. One of the things they brought with them was an expectation of what government was supposed to do, Mr. Perry said. As a result, the new residents tended to call police for assistance more often than the locals had.

As in other states, Vermont legislators reacted to what they perceived as an increase in crime by increasing penalties in an attempt to stem it.

The result, recalled former DOC Commissioner John Gorczyk in a telephone interview, was “an explosion in incarceration without an increase in crime.”

The DOC, in those days, was “underfunded, overcrowded and under-loved,” Mr. Perry said.

But young, idealistic officials were put in a position to make changes to the system when Governor Richard Snelling brought William Ciuros to Vermont to take over the DOC. Mr. Ciuros forced the department’s old guard out and installed “the new kids” in their place, Mr. Perry said.

Those included Joseph Patrissi, then deputy commissioner, Mr. Gorczyk, and Mr. Perry. Mr. Patrissi is currently executive director of Northeast Kingdom Community Action (NEKCA).

Mr. Ciuros got his deputies to cut their long hair and change their attire from woolen shirts to suits.

“We worked 12 hour days,” Mr. Perry recalled. “I never worked so hard in my life.”

Mr. Ciuros soon ran afoul of Governor Snelling and was dismissed, to be replaced by Con Hogan, but his team remained in place.

Among other initiatives, they started letting nonviolent offenders serve their sentences in the community, or on weekends, so they could continue working, Mr. Patrissi said.

That program hit a hard bump when the son of vice-presidential candidate Geraldine Farraro was arrested at Middlebury College with two and a half pounds of cocaine, said Mr. Perry.

He met the qualifications for release, except for having a residence in Vermont, Mr. Perry recalled. That was quickly managed, but the national media soon descended on Vermont to photograph the sign saying “luxury condominiums” outside his apartment complex, Mr. Perry said.

Madeleine Kunin had just been elected governor, and she tried to provide political cover for the DOC by creating the Community Corrections Advisory Board, Mr. Patrissi said.

She appointed Mr. Page to the board, as well as John Downs, a founding partner at Downs, Rachlin and Martin, and Fay Honey Knopp, a director of the Safer Society Foundation. The Safer Society program is a national referral service for sex offenders seeking therapy. She was also the founder of the Prison Research Education Action Program. Also on the committee was Jack Coleman, a former president of Haverford College who spent a sabbatical from his job as an inmate at a Pennsylvania prison. Mr. Coleman was a friend of the warden, who was the only one who knew he was there voluntarily, Mr. Perry said.

Mr. Patrissi and Mr. Page had already met, at a book club meeting at Mr. Page’s house on Willoughby Lake where both men spent summers.

After the meeting, Mr. Page, who knew Mr. Patrissi was commissioner of corrections, approached him.

“He asked, ‘How would you like to know something about human nature?’” Mr. Patrissi recalled. “I’d been in corrections 20 years and I was schooled in that side of human nature,” he said.

Mr. Page had been director of corporate planning at the Polaroid Corporation during that firm’s glory years and had learned from the work of E.O. Wilson, a sociobiologist and the world’s foremost expert on ants. Professor Wilson’s work, which traced the genetic basis of human nature, was being used by Polaroid in its marketing efforts, Mr. Patrissi said.

If Mr. Page decided someone was worthy of his attention, he’d latch on to that person as a teacher, said Mr. Gorczyk. Both Mr. Perry and Mr. Patrissi called him a mentor.

Mr. Page began running a kind of school for DOC officials, inviting them to his house, or taking them down to the Cambridge, Massachusetts, headquarters of Polaroid for classes with him or other experts.

As Mr. Perry recalled, he outlined some of the basic principles of human nature, including an innate fear of strangers, a preference for working in groups of around six members and, most importantly, the principle of reciprocity.

“If I buy you a drink at a bar,” Mr. Perry said to explain reciprocity, “you had better buy the next round. If I have to buy the second round, there won’t be a third one, and we won’t be friends.”

Working with Mr. Page and Mr. Downs, the group began to feel its way toward the system of reparative justice.

All felt that a real system of justice had to begin by putting the victim at its center, something that the English system of law, which was largely adopted by most U.S. states, did not do.

A reading of history, Mr. Perry said, shows the English originally had a system of law that rated the worth of an individual by his or her rank and punished offenses with fines that were proportional to the crime.

The basic idea, Mr. Perry said, was that a village needed all of its citizens if it was to function, so disputes had to be resolved in a way that would not cause the loss of someone’s skills to the community.

When William the Conqueror took over England in 1066, he assigned his son the task of creating a system of colonial law, Mr. Perry said. That law treated every crime as an offense against the king, who was presumed to own everything in the country. Fines were no longer paid to a victim, but were given to the king, and many crimes were punished by death or mutilation.

Vermont, in its Constitution, bans the latter form of punishment, which it calls “sanguinary punishment,” Mr. Perry said, so a system that turned away from the English model could be seen as being in accord with the intent of the state’s founders.

Mr. Perry found similar ways of meting out justice in such native societies as the Navaho, who resolve criminal offenses with a series of meetings or circles which seek to define the nature of the crime and gradually, through discussion, to find a way to mend the damage.

Whenever they hit a problem, Mr. Page would create a report that analyzed the situation in detail and proposed a solution, Mr. Perry said.

“He was right every damned time,” he recalled.

Mr. Patrissi said Mr. Page showed great patience with the group.

“Here we were, with this genius, who already knew where this was going to go,” he said. “We were in the hands of a genius.”

When Governor Snelling returned to office after Governor Kunin finished her last term, he called Mr. Patrissi in and demanded 12 great ideas, Mr. Patrissi said.

He liked the proposal for a reparative justice program and, after his sudden death, so did his replacement, Governor Howard Dean.

In order to figure out how to sell the program to Vermonters, the DOC wrote a grant and hired a polling firm to conduct the sort of market research that might be undertaken before a company like Proctor and Gamble launches a product, said Mr. Perry.

After conducting focus groups and an extensive telephone poll, the results were in. The people of Vermont hated the DOC, they also disliked the state’s attorneys, criminal defense lawyers and judges. They did like juries, though, Mr. Perry said.

“They trusted themselves,” he concluded.

Vermonters were also very positive about the reparative justice system when it was explained to them. The polls showed 92 to 94 percent favorability ratings, Mr. Perry said.

“Nothing gets 94 percent favorability ratings,” he said.

The first attempts at operating a reparative justice system were run through the DOC, but it soon became clear that the program would work better if it were handled by community members through an organization outside state government.

That led to the creation of community justice centers.

Over the years, the results of the reparative board have proved the worth of the idea. A 2007 study was hard to publish, said Mr. Perry, because journals found it hard to believe that recidivism could be reduced in Vermont by 26 percent through the process.

Since the creation of restorative justice programs, Vermont has been frequently visited by representatives from other states and other countries seeking to learn from the state’s experience.

Because Vermont has a unified corrections system, unlike other states with county, city and other government subdivisions running jails, its database is the most comprehensive in the country — a boon for researchers, Mr. Perry said.

Still, he and Mr. Gorczyk said they are not satisfied with the system as it exists. They feel it is underused.

Mr. Perry said he is pleased to see many schools are beginning to use the principles of restorative justice is dealing with infractions such as bullying. The results, he said, are very promising.

State law prohibits the use of reparative boards for some crimes, such as domestic abuse. Mr. Perry said he regrets that and believes the practice can achieve excellent results in those cases, if used properly.

Mr. Gorczyk said he has been pessimistic about the future of reparative justice until recently, but said the new Senate-passed bill is giving him renewed hope.

For Mr. Perry, it’s important to take the long view.

“We’re only 20 years into what will be a 100-year process,” he said.

This is the second of a three-part series on community justice. The first part was in the February 19 issue of the Chronicle, and can be read here.

contact Joseph Gresser at [email protected]

For more free articles from the Chronicle like this one, see our Editor’s Picks pages. For all the Chronicle’s stories, pick up a print copy or subscribe, either for print or digital editions.