copyright the Chronicle February 26, 2014

The Problem of Slavery in Early Vermont, 1777-1810. By Harvey Amani Whitfield. Published by the Vermont Historical Society 2014. 140 pages with notes, documents and index. $19.95

Reviewed by Paul Lefebvre

The assertion that Vermonters kept slaves into the early years of the nineteenth century not only skews the state’s constitutional ban on slavery but also calls into the question the historical belief we have of ourselves as a people who believe in live and let live.

Surely there can be no place for such a belief where men can live off other men’s labor and sell their children. But that’s what historian Harvey Whitfield has found and documented in his new book, The Problem of Slavery in Early Vermont, 1777-1810.

For those who don’t have the date on the tip of their tongue, 1777 was the year Vermonters formed a Constitution that abolished slavery. Well, not quite. What the framers actually abolished was adult slavery. The children of the new black freemen could still be for sale.

Like the Declaration of Independence, the Vermont Constitution starts off on a lofty note:

THAT all men are born equally free and independent, and have certain natural, inherent and unalienable rights, amongst which are the enjoying and defending life and liberty; acquiring, possessing and protecting property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.

But then the fly in the ointment appears: Therefore, no male person, born in this country, or brought from over sea, ought to be holden by Law, to serve any person, as a Servant, Slave or Apprentice, after he arrives to the age of twenty-one Years, nor female, in like manner, after she arrives to the age of eighteen years, unless they are bound by their own consent, after they arrive to such age, or bound by Law, for the Payment of Debts, Damages, Fines, Costs, or the like.

Whitfield sounds either cautious or charitable when he explains the loopholes of emancipation in the Republic of Vermont of 1777: “Those who drafted Vermont’s constitution expressed more of a wish for than an actual prohibition of black bondage.”

Vermont’s special conditions of emancipation presumably come as no surprise to the professors and students of the state’s early history. But for whatever reasons, it has fallen to a UVM history professor with an interest in “the black population in the Maritime colonies” to meticulously document how slavery continued to co-exist with a wink and a nod among nearly all classes of Vermonters.

On a webpage for college students to rate their professors, one described Harvey Whitfield as “literally the most amazing professor I’ve ever had at this school. I have no words. Please for the love of GOD take a class with this guy.”

That’s pretty high and rare praise from a college student. And no one reading this book will have any doubt that Professor Whitfield is a teacher who knows his stuff. Unfortunately he is not a storyteller. The book is disappointingly short of narrative but extremely dense with primary documents, which, admittedly, is hardly a liability for someone writing history.

And what a history early Vermont turns out to be when it comes to its struggle with race and slavery. Late eighteenth-century Vermont was a mixed bag when it came to slavery: some blacks owned property and voted, while others were kidnapped and enslaved.

History is seldom one thing or the other. Whitfield writes: “Opportunities for both black freedom and the persistence of slavery existed in the complex world of early Vermont. Powerful wealthy men defied the constitution by keeping slaves without any fear of retribution.

“Slavery persisted in the open and remained sanctioned by some local elites throughout the late eighteenth century,” he writes.

There were exceptions, however, for those who had the right mixture of pluck and opportunities. The author provides an account of the slave who in 1779 sued in a Vermont court for his freedom and won.

One of the most intriguing passages in the book traces the roots of slavery and race in eighteenth century Vermont to the fight for political independence. Slavery for the Green Mountain Boys stemmed from a loss of political independence and property.

Whitfield quotes Ethan Allen using the specter of slavery as a condition that befalls those who are conquered by a foe, which in much of eighteenth century Vermont was New York. In preparing for the pending struggle with the Yorkers, Allen in 1785 wrote:

“If we have not fortitude enough to face danger, in a good cause; we are cowards indeed, and must in consequence of it, be slaves.”

It was that kind of attitude, says Whitfield, that formed the basis of eighteenth century racism. The blacks had become enslaved as a people because they had lacked the bravery to prevail.

“Allen clearly asserted that possessing courage and bravery, one will not become enslaved, while those who lack honor and bravery will become slaves, and deservedly so.”

Early in the text — which only consists of 41 pages of narrative, essentially a monograph — Whitfield notes that the “end of Vermont slavery was contested, contingent, complicated and messy.”

It was also paradoxical as Whitfield suggests that in order to separate itself from New York as far as politically possible, Vermont took the step to abolish slavery in its Constitution.

“Perhaps more than in any other part of America, Vermonters acutely felt the prospect of political slavery to a neighboring state, which literally threatened to take away their property and some of their natural rights,” writes Whitfield.

And because New York had the largest slave population of any of the northern states, he argues that Vermont’s move to ban slavery made it radically different from its neighboring state to the west.

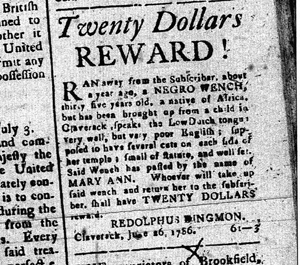

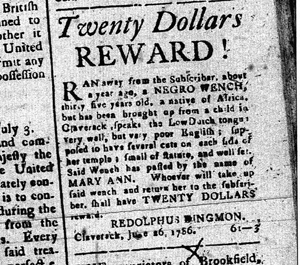

To trace slavery’s longevity in Vermont, the author uses bills of sales, the federal census for 1791, probate court records, and newspaper ads offering a reward for a runaway slave, such as the one offering a $25 reward for the return a NEGRO WENCH, 35, that appears in a 1786 copy of the Vermont Gazette. Whitfield contends the ad underscores how tolerant the public attitude was toward slavery.

“Slaveholders would not have advertised in Vermont newspapers if they had little hope that local inhabitants might help them regain escaped slaves.”

The book contains reproductions of many primary sources and documents, including the 1810 census showing that 33 years after slavery was constitutionally banned, two Vermonters still owned one slave apiece.

contact Paul Lefebvre at [email protected]

For more free articles from the Chronicle like this one, see our Reviews pages. For all the Chronicle’s stories, pick up a print copy or subscribe, either for print or digital editions.