copyright the Chronicle July 18, 2012

by Richard Creaser

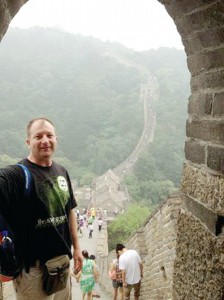

LYNDONVILLE — Sitting in a booth at the Ms. Lyndonville Diner, Canaan Memorial High School English teacher Jason Di Giulio of Sheffield sipped at his coffee, his mind racing to organize ten days worth of recent experiences in China. Mr. Di Giulio, a 2011 winner of a National Education Association (NEA) excellence in teaching award, traveled to China to explore the country and its educational system. He and 34 other NEA Foundation winners spent ten days there between June 19 and 29.

Winning a trip to the Orient may seem like a just reward for some of the nation’s hardest working educators. But this was no pleasure junket. Sponsored by the NEA Foundation, the Pearson Foundation and Education First, the purpose of the trip was to expose the teachers, also known as Global Learning Fellows, to a country and culture that few Western students have occasion to see firsthand.

“The purpose of this trip was to raise global awareness,” Mr. Di Giulio said. “Students need to understand that we are living in a flat world. The competition for jobs isn’t coming from Massachusetts or Connecticut or Maine, it’s coming from China.”

While in China the Global Learning Fellows met with representatives of FASTCO, the Chinese based manufacturer for Fastenal, as well as representatives from Intel Corporation. They learned that what international corporations want and need are independent thinkers who are capable of responding quickly to changing circumstances.

“It’s not something that the Chinese educational model really encourages,” Mr. Di Giulio said. “I think of the Chinese educational model as a factory model — everyone comes out of it knowing what they need to know to do the job they have prepared for. It’s a model based on rote memorization and testing, with testing being proof of success.”

But a system based on knowing and retaining specific information does not encourage free thinking. That’s the one area where the Western educational system may hold a distinct advantage over China, Mr. Di Giulio said.

Gradually, the U.S. appears to be moving toward that same model with standardized tests that create an objective measure of success. But at what cost?

“What we learned is that the factory model doesn’t take into account what employers are looking for,” Mr. Di Giulio said. “We need to develop and refine our curriculum to include more problem solving and critical thinking. We need to be able and willing to teach several methods and allow students to adapt to the model that best fits their learning style.”

The Chinese focus on excellence is bred from necessity and was exemplified not only in the classrooms but also in the everyday world, Mr. Di Giulio said.

“The only students we saw at the vocational school and the middle school were the students who conform to the idea of the norm,” he said. “The students who were perceived as below the norm went to their own school. This is quite the opposite of what we are trying to do here in the West.”

Mr. Di Giulio spoke of the morning he ordered an omelet from the hotel kitchen. It took the cook three tries to produce an omelet worthy of his guest. To Mr. Di Giulio’s eye, any of the three would have sufficed.

“That’s the kind of pressure they have in the job market there,” Mr. Di Giulio said. “If you can’t do the job, there’s always someone else, a billion someone elses, waiting to step in. That creates tremendous pressure to be the absolute best at whatever it is you do.”

Striving to be the best certainly isn’t a bad thing, Mr. Di Giulio stressed. But the important part is the striving and not necessarily the success.

“Innovation is about taking risks, and taking risks means that sometimes you will fail,” he said. “Entrepreneurship is about taking a risk, and if it doesn’t work, you try again. When you are focused entirely on success as the end result you become unwilling to take any risks and innovation suffers.”

The Chinese model has plenty to offer to Western educators both for what it does right as well as where it falls short. Educators who are focused on a specific subject and who have adequate time to prepare and deliver instruction can achieve better results. And when the entire family promotes and supports a student’s education, chances of success are exponentially higher.

Chinese teachers deliver instruction in a single 80-minute class once per day. They devote the remainder of their time to preparing for the next day’s class and reviewing test data. This is in marked contrast to American teachers who spend most of their day with their students and who do some of their preparation during free time in the school day with the balance taking place at home.

“The temptation is there to say that their system is working,” Mr. Di Giulio said. “With focused dedication, parental and political support, students can achieve great things. But there is also a warning to be had.”

The suicide rate among high school seniors is troublingly high. Many students feel smothered by the inescapable cultural pressure to excel.

“In China the mandatory retirement age for men is 60 years old and 55 years old for women,” Mr. Di Giulio said. “It is also expected that the children will take care of their parents in their old age. In the era of the one child policy, that means that a couple must earn enough to support not only themselves and their child but also up to four parents.”

In a country that boasts as many honor students as the U.S. has students, the competition to land positions in the best universities is fierce. In China a university education spells the difference between a poor-paying job as a laborer or access to a coveted job in the middle class with room to advance.

“I don’t think we fully appreciate how important access to higher education is in this country,” Mr. Di Giulio said. “The difference here is that, as long as you are willing to find the money or carry the debt, eventually you will be able to get into a university. In China, if you can’t get into a Chinese university or can’t find the money to attend a school overseas, you don’t have many options left.”

The Chinese system puts tremendous pressure on students with its focus on testing and measurements of success, but in some ways the Western educational system is working toward an opposite extreme.

“There has to be some happy medium between rote memorization and measured achievement and creativity, hugs and self-esteem,” Mr. Di Giulio said. ‘There is certainly a group that is willing to shout and say that our educational system is broken. If I look at the results of my students and see what they have achieved, I know it’s not broken.”

Finding an objective standard to measure American students against was a laudable but ultimately doomed element of No Child Left Behind (NCLB), Mr. Di Giulio said. The idea that all students would be suitably proficient in all areas by 2014 was an admirable goal. The trouble was that the goal faced barriers test data doesn’t measure.

“If I could ensure that every kid had three good meals a day, had their parents read to them since they were two years old, got enough sleep and received proper medical care, and their schools were fully funded, I would say achieving 100 percent proficiency was entirely possible,” Mr. Di Giulio said. “But that’s not the world we live in. The law alternately encourages or disciplines schools for failing to meet the challenge without addressing the underlying causes.”

The system is further flawed by allowing each state to set its own standards. Although intended to measure and compare students around the country, the lack of common standards makes the comparisons ultimately futile, he said.

“Until we take into account the global standard that our students are being measured against, we really can’t accomplish anything truly meaningful,” Mr. Di Giulio said. “We do need to adopt a universal standard that recognizes what every student needs to know in order to become successful Americans.”

He said he plans to incorporate less fiction and more analytical works in his own instruction. Developing a stronger ability to problem solve and enhance analytical skills is critical if American students are to compete in the global marketplace.

“Creative thinking and the ability to adapt to changing circumstances is, and should continue to be, the focus of the American educational system,” he said. “In order to do that, we need a better understanding of the world. It’s no longer about competing for jobs with students in Michigan or California. It’s about competing with students from China and India and other parts of the developing world.”

contact Richard Creaser at [email protected]