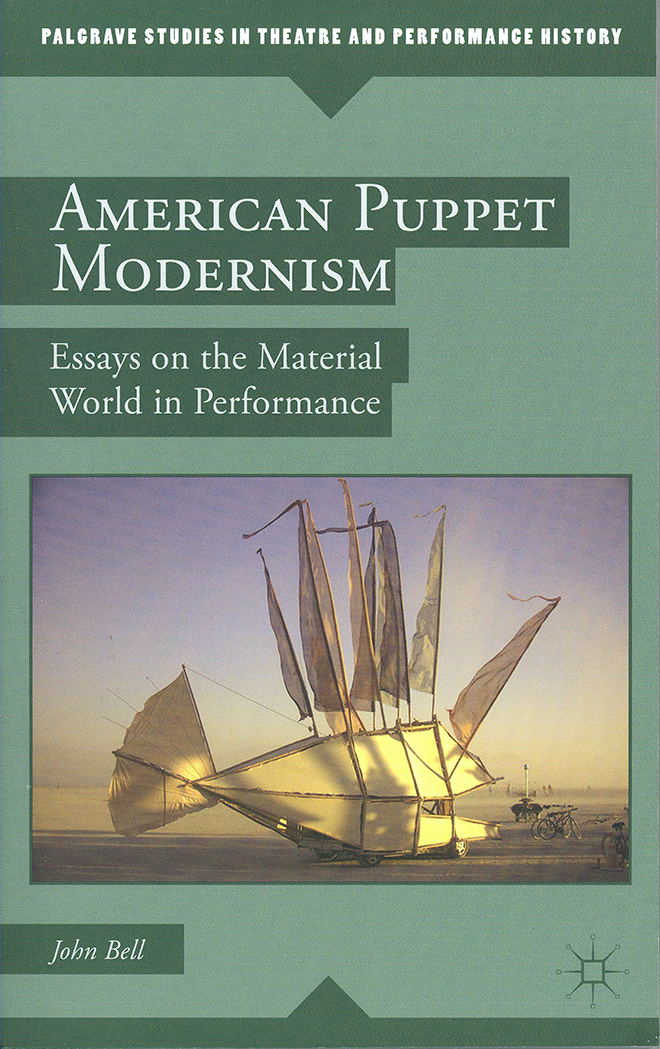

American Puppet Modernism: Essays on the Material World in Performance, by John Bell. Published by Palgrave MacMillan, New York, 2013; 280 pages, softbound, $28.00.

American Puppet Modernism: Essays on the Material World in Performance, by John Bell. Published by Palgrave MacMillan, New York, 2013; 280 pages, softbound, $28.00.

Reviewed by Joseph Gresser

copyright the Chronicle 1-29-2013

When most people think of puppets the image of Jim Henson’s Muppets probably springs to mind, followed, if they live in northern Vermont, by the creations of Bread and Puppet Theater’s Peter Schumann.

Puppeteer and scholar John Bell wouldn’t disagree with those thoughts, but in American Puppet Modernism, first published in 2008 but just reissued in a softbound edition, he argues for a much broader view of the field. For Mr. Bell, puppets are a particular example of “object performance,” and his fascinating collection of essays examines the implications of the theater of things.

Object performance, Mr. Bell explains, encompasses all manner of familiar and unfamiliar theater, from masked performances to the balloons in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade and beyond.

The book starts with a description of a traveling show in the late nineteenth century that, by means of illuminated paintings and a spoken narrative, told the story of a conflict between native Americans and European settlers in Minnesota. As one might expect, the story reflects the view of the settlers, depicting Indians as savages.

That view is slightly modified when early ethnographers visit the Zuni Indians in the southwest several years later. There two observers record religious rites involving giant Shaklo figures, tall rod puppets who mediate between the human and spirit worlds.

Mr. Bell shows how the views of the two observers are to varied degrees clouded by the assumption that the Zuni people are barbarians, midway on the journey from being savages to being completely civilized.

Literary critic Edmund Wilson, seeing the same ceremonies a few decades after the ethnographers, though, is able to see the force of the puppets’ performance and its position as the glue that holds Zuni society together.

Mr. Bell argues that American society is bound together in a similar, if less pure, fashion by performing objects. The puppets that performed on a stage modeled after a giant medicine cabinet at the 1939 World’s Fair were there to tout the advantages of modern pharmaceuticals, and similar performances sought to persuade consumers that the world of the future would be one dominated by automobiles.

That future has come to be, and Mr. Bell takes a close look at how people use automobiles as performing objects. His chapter about hot rod culture casts a new light on the idea of performance cars, by showing how customizing an automobile to increase its speed and to give it a distinctive appearance makes the vehicle a player in the driver’s self-presentation.

In addition to exploring the byways of object theater, Mr. Bell gives a straightforward history of how puppets became a prominent feature of modern theater. From its introduction as part of the Little Theater movement in the Midwest, and eventually around the country, he traces outbreaks of puppetry in opera, theater and, eventually television.

In Europe, puppetry was seen as a less than respectable form of theater, Mr. Bell says. Puppeteers were able to satirize rulers and other important figures, often escaping punishment by insisting that it was the puppet, not the person, doing the mocking. That idea of object theater being a somewhat lower-status form was one that was carried over in puppetry’s journey to the United States.

The very word puppeteer was invented around 1917 by theater pioneer Ellen van Volkenberg. The term was modeled on the word muleteer, a very appropriate choice considering that puppets can be notoriously recalcitrant.

Although the Little Theater movement died out, a number of the puppeteers who got started in its productions went on to become major forces in theater and the commercial world.

The inflatable balloons in the early Macy’s parades were created by puppeteers who were always willing to investigate new materials for their creations. (One of the wonderful facts Mr. Bell drops into his story is that in the first years of the Macy parades, the puppets were released as part of the festivities, to the consternation of airplane pilots.)

Mr. Bell includes in his survey of object theater the cinematic puppetry that brought King Kong to life. Film, he argues, is analogous to shadow puppetry as practiced by Indonesian and Chinese artists. The technology of computer graphics and motion capture technology that is essential to the effects that animate films today is a further extension of puppetry, Mr. Bell argues.

He gives a list of the biggest moneymakers in film history, all of which include computer generated creatures. His book was written before the film Avatar broke box office records, but it would have taken his point further in that the human hero could himself be seen as a puppeteer, bringing an alien character to life in order to fit into a nonhuman civilization.

As a former member of the Bread and Puppet Theater, Mr. Bell speaks of Peter Schumann’s work with insight and sympathy. Oddly enough, he chooses as an example a show in which I performed in 1995. Mr. Bell’s clear description was particularly interesting to me because, working behind large pieces of cardboard throughout the evening, I never could see even an approximation of what the audience witnessed.

Mr. Bell contrasts Mr. Schumann and Jim Henson, who once shared studio space in New York City. Mr. Schumann has sought freedom for his artistic and political vision by pursuing the least expensive means to create a spectacle.

Mr. Henson, whose vision of the world Mr. Bell suggests was sunnier than that of Mr. Schumann, was willing to accommodate himself to a commercial system in order to get his message across.

In his book Mr. Bell makes clear how this dichotomy has inhabited object theater over the past century or so, and how the practitioners of the art of puppetry have tried to overcome the physical and societal limitations to pursue their vision.

contact Joseph Gresser at [email protected]

For more free articles from the Chronicle like this one, see our Reviews pages. For all the Chronicle’s stories, pick up a print copy or subscribe, either for print or digital editions.