copyright the Chronicle 12-26-2012

copyright the Chronicle 12-26-2012

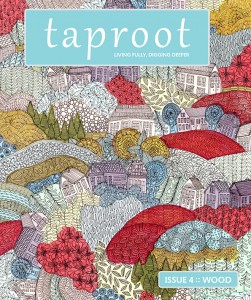

The following is an excerpt from an article written by Julia Shipley of Craftsbury for a new magazine based in Hardwick called Taproot. The magazine comes out four times a year and each issue is based on a theme. Its motto is “living fully, digging deeper.” The magazine seeks to publish high quality writing, photos and art from local and national writers on topics related to what would have been called, a generation or two ago, the back-to-the-land movement — an effort to get back to basics in matters of food, home life, work, and more. “We didn’t see media that addressed this nascent movement in any meaningful way,” said publisher Jason Miller. The magazine has no advertising, except it ran an insert for natural toys in one edition. Its goal is to pay for itself by subscriptions, which are $30 a year. In the most recent issue, the theme was wood. Cover art was by Maine artist Jennifer Judd-McGee. Single copies are available at the Galaxy Bookshop in Hardwick. For more information, see the magazine’s website: www.taprootmag.com. For more information about Julia Shipley, take a look at www.thenewsfrompoems.com where she writes about poetry, and www.writingonthefarm.com

by Julia Shipley

On the upper west side of Manhattan, on the first floor of the Museum of Natural History, sequestered in a dim corner is a slice of a mammoth sequoia, God’s torso, I think as I gawk at this hunk which germinated from an infinitesimal seed in the year 550 AD, the year St. David converted Wales to Christianity. The year it was cut down, 1891, was the year the zipper was invented. None of us staring at this shard of a sequoia had even been born yet.

When it was exhibited at the Chicago World’s Columbian Exhibition in 1893, according to the museum’s docent, people were incredulous that a tree could ever grow so big, and disgruntled that it had been severed for their viewing pleasure.

The cross section — displayed on end showing the growth rings, all 1,342 of them, one for each year of the tree’s life — is broad as a Cadillac Coup de Ville and tall as a UPS truck. Were it to somehow flop over and appear as it had in the forest the day it was finally cut from the stump, its dimensions would match that of our town’s stout gazebo, a lone edifice on the Common where small orchestras play in the summer. In my mind’s eye I grow the gazebo into a sequoia tree that looms hundreds of feet over the town ground.…

Stuart LaPoint, the owner of a landscaping business and assistant tree warden for the town of Craftsbury, gets around — meaning he drives the back roads a lot, keeping an eye out for something big. In 2010 he put together a group of photographs showing 12 of Craftsbury’s most majestic specimens. After some pestering (I’d rib him when I saw him at the general store, “Hey, I’d love to go check out those trees.”) he agreed to let me come along.

It helps I happen to have two of the biggest trees in town, or rather, they have me, whichever way you look at it: they are the oldest things I live with — these huge red oaks, with limbs as tall and thick as regular trees. In the fall when they’re tawny, the one on the left has goldish leaves, and the one on the right’s are more russet. As I spend the weekends of October and November raking up their endless bequest, I ponder how old they are.…

So one day in March, when Stuart calls up and asks, “How’s tomorrow?” I tell him it’s perfect. We are going to visit the biggest living trees he knows about within five miles of the town gazebo. He’s called all the landowners; we’re cleared to visit.

As he pulls in the driveway the next morning, my big oaks throw zebra stripe shadows all over his pickup truck. As we gaze 70 feet up into the trees’ canopy, I tell Stuart how recently a tree- size limb wrenched loose and how I hired a guy named Karl Nitch to help take it down and how Karl used tree spikes to climb 60 feet up and fell the monstrous limb. The whole time I worried what I might have to say to Karl’s surviving wife, but in the end, he returned to the ground of his own accord and I had enough bucked up chunks to heat the house for half the winter, and to give to my neighbor Dave Brown, who churned out eight oak bowls on his lathe. As my Dad and I split firewood together, we marveled at the pretty pink flesh of the oak — oh, so this is why they call it “Red.” And when folks come over for dinner, I’m sure to tell them how these bowls grew in the yard.

The second stop on our tree tour is just up the road, by the Whitney Brook, and there it is: strong, straight and tall, growing impossibly from the bank of the brook. Standing beside it you can see the Atwoods’ silo and the power pole running current up to the barn.

Stuart announces, “It’s a hoyt spruce.”

A hoyt spruce?

“Yeah.”

“Hoyt?”

“Hoit.”

Oh, you mean ‘white’?

“Yup, and 32 feet high if I had to guess. You’ll look hard to find one bigger. Should live another 30 years. I just happened to see it from the road one day as I was going by.”

And then, quick as a wink, we are back in the car headed further up the Creek Road toward Albany, to get a look at Bruce Butterfield’s hop hornbeam (also known as ironwood) off near a clearing, and then his American Linden (also known as basswood).

Standing beneath the Hornbeam I am blasé — its stature seems unremarkable, neither broad nor tall, but as I learn later reading Donald Peattie’s A Natural History Of Trees of Eastern and Central North America, my nonplus is dipped in ignorance, as Peattie writes, “Only occasionally does this tree grow 30 feet high,” and here Stuart has located this “occasion” right in our neighborhood. Meanwhile, he defends the linden growing nearby, stating, “I don’t think that it’ll be a wow-er, but it’s pretty big — look on the trunk, it’s got some girth, close to 42 inches I’d guess.”

On with the tour, we buzz back toward town, merely driving by the jumbo paper birch on the roadside near Ron Geoffroy’s East Hill Auto and the quaking aspen in the bank by the Midis 20 feet from the intersection of South Albany and Ketchum Hill Road.

So often I simply see “trees” and not individual species, as in a stadium I simply see “people,” a human blur. When I moved to Craftbury eight years ago, the town was full of blurry people, but in the intervening years, or in arboreal terms: eight growth rings, I’ve learned names and personalities, so it is fitting that each tree Stuart introduces is linked by its name to a neighbor, as I start to see the forest through the trees….

“In the early days of pioneering in the northeast, the “land-lookers” brought back tales of a tree of gigantic height, which grew in the wildest and remotest recesses of the great North Woods”— Donald Peattie A Natural History of Trees of Eastern and Central North America.

The last time Jim Moffatt saw the yellow birch was about a year ago. These last few years he’s gotten behind on some of his winter woods-work — and counting backward, he’s had five hip operations; then there was a winter with so much snow he couldn’t get into the woods, so he took his skidder apart to make some adjustments and put it back together; and the winter before that he spent going down to Fletcher Allen Hospital in Burlington to take his wife, Joan, to her appointments.

As we climb into his Ford pickup, Mr. Moffatt tells me he was born in the house. The land came into the Moffatt family when Jim’s father bought the estate from Daniel Dustan, a descendant of the founding families of Craftsbury. And Mr. Dustan had purchased the parcel containing the Yellow Birch upon his return to Vermont after a stint in the South at outset of the Civil War. In a diary kept by Mr. Dustan, he describes building a sugarhouse. Back then, the yellow birch must have been surrounded by giant sugar maples. To form into a soaring tree, straight and tall, the yellow birch had to bide its time in the shade of older trees, and then shoot up, “released,” as the others died off.

We are driving north through Moffatt’s Tree Farm. Acres of Christmas trees grow on both sides of the road. What began as a sideline enterprise to dairy farming when Jim’s father started cutting wild balsams in old pastures has turned into a full-time cultivated tree farm operation under Jim’s management. Now Jim’s son Steve is responsible for 100,000 trees on parcels of land spread out over five towns.

We travel down a side road and pull over as Jim hops out to open the gate across his right of way, then climbs back in. Entering the leaf-shingled shelter of the woods, we lurch along a cobble-cluttered skidder road. Jim recollects, “The first time I looked at the yellow birch was in the 1960s after I bought the parcel from my father…. I thought there was some lumber in it, but it was too much, more than my equipment could handle to bring it down.”

Though Jim’s father never mentioned it at the time, he too knew about the yellow birch. Eventually Jim learned his father had seen it years before and also thought it large, too large to take down with the equipment they had.

Back in 1972, a man named Jeff Freeman, then a professor at Castleton State College, began making a list of Vermont’s largest trees. In 2001, Loona Brogan of Plainfield, Vermont, founded the Vermont Tree Society, a group and website celebrating Vermont’s largest trees. And now the most up-to-date list, with more than 110 species and varieties, is maintained by Vermont Department of Forests, Parks and Recreation. Jim Moffatt’s tree is not on this list. There is an even bigger yellow birch in Victory. But Jim’s may be the oldest.

“It must be three hundred years old. I’m 75 and it is relatively unchanged in my lifetime.”

We get out of the truck and walk a ways up the road, and then he stops and says, “There.” Though it sits back amid the woods of other sturdy trees, I am absolutely certain which tree he means.

It’s like coming across an I-beam in a box of tooth picks: it rises with authority; and it has a demeanor, emanating a sort of warmth and feeling, the way a person does. It seems far more sentient than anything else around it and indeed, it has convinced three centuries of appraising men that it’s not meant to be felled by saw.

When Jim leans against the yellow birch’s broad trunk for a photo, he does in a companionable way, and lets the trunk take some of his weight, an intimate gesture, more personal than simply standing beside it; and he favors the right side of the trunk, as opposed to the center, as if to leave room for where Joan would have stood, or still is standing, in some way.

Peattie concludes his chapter: “Frequently when a yellow birch comes to the end of its life span, it stands a long time, though decay is going on swiftly under its bark.”

Jim puts this truth another way, “You can see the inside’s rotten — one day the winds are going to bring it down.”

As we back away I ask, “Does it have a name?” — as the cypress was called the Senator or the chunk in the Museum of Natural History was from a tree named Mark Twain.

“No, it’s just the yellow birch.” After a pause he adds, “But if it did, I guess it would be ‘Joan,’ after my wife, as it represents so much about our our lives together.”

Then, once more, as has happened for hundreds of years, we turn away to leave, and the yellow birch remains.

I like to imagine one day, Steve’s boys, Jim’s grandsons, will grow up and bring their children here.

On page 36 of the 2011 town report, the Craftsbury Municipal Forest Committee notes that Stuart LaPoint received a grant from the Preservation Trust of Vermont to plant 12 trees. He planted one in the village and then tucked in 11 others on the Common, surrounding the lone gazebo and the hidden-in-plain-sight ancient maple. Stuart planted red maple, river birch, flowering crab, blue beech, hop hornbeam, Princeton elm, Japanese tree lilac and serviceberry. How about that? The man cruising the roads looking for the biggest and oldest being in the woods, is also cruising through town making sure the youngest have a chance to grow into something substantial, maybe even large, maybe even old, and hopefully recognized years, decades, maybe even centuries from now.

For more free articles from the Chronicle like this one, see our Featuring pages. For all the Chronicle’s stories, pick up a print copy or subscribe, either for print or digital editions.